Category: Writing

-

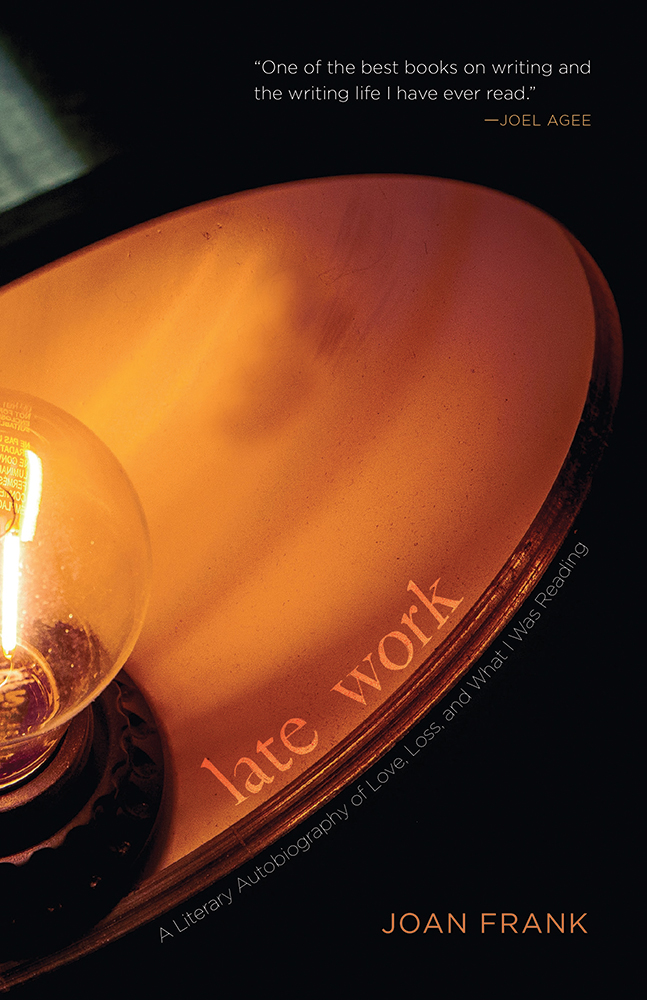

Late Work

Late Work: A Literary Autobiography of Love, Loss, and What I Was Reading

Joan Frank

University of New Mexico Press 2022Reviewed by Bob Wake

Few writers are as honest and uncompromising about their art as Joan Frank. The essays collected in Late Work: A Literary Autobiography of Love, Loss, and What I Was Reading address “writers who’ve been at it awhile.” Readers and writers at any stage will find it both inspiring and sobering to learn that one of her novels, The Outlook for Earthlings, took fifteen persevering years to find a publisher.

Frank disputes the notion that writers and introverts in general are somehow better equipped to withstand the isolating effects of a global pandemic. In “Make It Go Away,” the COVID lockdowns are depicted in all their hallucinatory disorientation. “We’ve had terrible trouble sleeping,” she writes. “We’ve felt spaced out or angry or glum, tired or twitchy, scared or numb or listless…”

She admits to a post-pandemic loss of “clarity and conviction” (“It Seemed Important at the Time: The New Doubt”) and suggests the feeling may be more widespread than we realize. Her cultural analysis is persuasive. Frank’s New Doubt, like Hunter Thompson’s fear and loathing, portends bad vibes ahead:

Why lie about the sad drooly bony smelly Black Dog plopping down upon one’s chest at all hours, groaning and farting in its nightmare-riddled sleep?

Late Work is wide-ranging. Other highlights include an encomium to the practice of letter-writing (“Just anticipating letter-writing is erotic for me—the way approaching a bloc of private writing time and space is erotic”), and a bookstore reading gone horribly wrong (“Gird yourself, earnest artist. When attention comes it will contain naysayers”).

Two essays are devoted to the “now-classic-but-once-unknown” 1965 novel by John Williams, Stoner, about the struggles and muted transcendence of a Midwestern literature professor. “The novel’s arc feels—like all our very greatest art—inevitable,” Frank writes. “Its particulars shine with the relevance of the universal. It is timeless.”

The advice to writers in her essay “What Are We Afraid Of?” becomes advice to anyone feeling unmoored right now. “Despair can paralyze,” she warns. “If we’re paralyzed, nothing gets made.” We must teach ourselves to “shut out the roar.” Joan Frank offers strategies to help us find our way back to doing the work we care about.

-

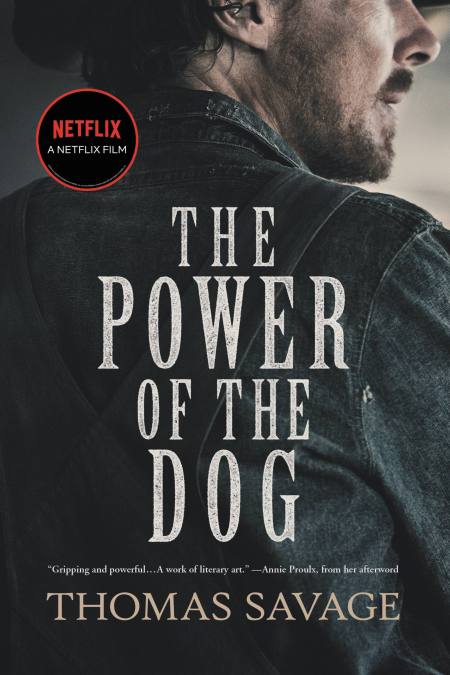

The Power of the Dog

The Power of the Dog

Thomas Savage

Afterword by Annie Proulx

Back Bay Books 2021 [2001]Reviewed by Bob Wake

Back Bay Books’ 2001 reprint of Thomas Savage’s 1967 Western novel, The Power of the Dog, with a laudatory afterword by Annie Proulx, brought serious reconsideration to Savage’s largely forgotten book. (Not unlike the rediscovery of John Williams’ Stoner from 1965, recognized only in the last ten years as a classic American novel.) New Zealand director/screenwriter Jane Campion’s adaptation of The Power of the Dog, and its twelve Oscar nominations, should further burnish the book’s reputation. As Proulx writes, “Savage created one of the most compelling and vicious characters in American literature.” That would be Phil Burbank, played with menacing brio by Benedict Cumberbatch. Montana ranch owner, bully, and sexually repressed homophobe. “He is, in fact, a vicious bitch,” says Proulx. Ahead of its time? Possibly. But as a revisionist Western, even an anti-Western, Savage’s novel precedes Robert Altman’s McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971) by a mere four years. Campion gets it. Kodi Smit-McPhee, in one of the best fakeout performances in recent years, seems to consciously echo Keith Carradine’s brief but unforgettable role in Altman’s film as a bumpkin out of his depth. What really seals the homage is Carradine’s cameo as the governor in Campion’s film.

-

Sustainable Living

Sustainable Living

Elsa Nekola

Willow Springs Books 2021Reviewed by Bob Wake

Wisconsin writer Elsa Nekola’s debut collection of short stories, Sustainable Living, is so deeply knowing of the Upper Midwest that it functions as a kind of wisdom literature. Granted, the wisdom may not always be welcome. Disillusionment is a recurring theme, as is the fictional town of White Birch, where old habits die hard. A retired supper club owner (“Winter Flame”) can’t quit his mealtime routine of “folding his cloth napkin into a swan.” The betrayal of a fragile summer friendship (“River Through a Half-Burnt Woods”) replays itself in a woman’s memory like a wound that refuses to heal.

Fifteen-year-old Coral, the protagonist of “Oktoberfest,” feels preternaturally at home in the Northwoods, but less so in an adult world of struggling families and economic hardship. Addiction. Unwanted sexual attention. “She’s beginning to think,” we’re told, “that being a woman means staying where you’re needed, not where you want to go.”

Coral, by story’s end, may not know where she wants to go, or where she fits in. But readers will recognize in the achingly fine-tuned descriptions of landscape and wildlife that Coral has a near-mystical connection to her surroundings:

Today, there’s frost on the grass, and a chill that won’t leave the air until April. The mallards and black ducks have begun to court, and in midwinter the hairy woodpeckers will drum on hollow trees.

Nekola is especially good on the complexities of mother-daughter relationships, whether a grown daughter in “Meat Raffle” returning from Chicago to visit her eccentric literary mom in southeastern Wisconsin (“She thinks she’s the first sixty-year-old widow to discover Shakespeare,” fumes the daughter), or the title story’s resourceful fourteen-year-old Myra Pavelka, abandoned to relatives and afternoon barrooms when her mother hastily takes flight under possible criminal circumstances.

Sustainable Living won the 2020 Spokane Prize for Short Fiction from Willow Springs Books, whose top-notch book design compliments the jeweled precision of these stories. Elsa Nekola’s work has appeared in numerous literary journals, from Ploughshares and Passages North, to Rosebud Magazine and Midwestern Gothic.

-

A Swim in a Pond in the Rain

A Swim in a Pond in the Rain: In Which Four Russians Give a Master Class on Writing, Reading, and Life

George Saunders

Random House 2021Reviewed by Bob Wake

An unexpected delight. Sure to become a classic on the craft of short story writing. George Saunders’s discussions of the mechanics of seven Russian short stories (three by Chekhov, two by Tolstoy, and one each by Gogol and Turgenev, all included in the book) are so clear-eyed and openhearted as to be breathtaking. Additionally filled with revealing insights into his own idiosyncratic stories and his development as a writer. Jonathan Franzen attempted something similar in 2013 with The Kraus Project, his heavily annotated collection of essays by the Viennese satirist Karl Kraus. While Franzen’s autobiographical asides were disarming, the Kraus texts themselves were nearly impenetrable to modern readers. Not so with the Russian short stories collected here, which remain touchstones of high literary art, Shakespearean in their universality and timelessness.

-

Two by Joan Frank

Where You’re All Going

Four Novellas

Joan Frank

Sarabande Books 2020Try to Get Lost

Essays on Travel and Place

Joan Frank

University of New Mexico Press 2020Reviewed by Bob Wake

The publication of two new books from writer Joan Frank offers readers a not-to-be-missed opportunity to experience the range of her literary gifts. The four novellas in Where You’re All Going demonstrate the author’s eye for observational and psychological detail. Frank’s characters, no matter their documented flaws or shortcomings, are often mesmerized and transported by music and art. A character swooning in revery describes jazz singer Johnny Hartman as having a “blackberry-syrup voice.” Viewing portraiture by the painters Thomas Eakins and John Singer Sargent is “like a form of time travel.” Observational and psychological detail are also the qualities that bring an immersive richness to her travel essays in Try to Get Lost. She spurs herself, and all of us, to follow “Henry James’s injunction—to be someone on whom nothing is lost.” While adding, with the flinty wisdom of a seasoned traveler, “Understand you will continue to fail spectacularly at this.” (“Resolve it anyway,” she advises.)

Frank’s well-received 2017 novel, All the News I Need, introduced us to one of the most memorable characters in recent literature. Splenetic, yet fulsomely life-affirming, Frances “Frannie” Ferguson. Frannie reappears in Where You’re All Going, in the novella “Open Says Me.” Retired and unmoored in Northern California since the death of her husband, Frannie marks time, literally, singing and performing with a local choral group. Music sustains her. Buoys her. (“Melodies like currents, pushing away everything that is not them.”) Deliriously profane. “Christ on a cracker,” is a milder locution. An imbiber of whatever’s on hand, such as diet ginger ale laced with “long quantities of Cuervo Gold.” Frannie’s attraction to a thirty-something D.J. is fueled less by alcohol and poor judgment than enthrallment to their shared deep-cut knowledge of American pop music. She invites the D.J. to a choral concert and an after-show meet-up. Humiliation and self-loathing ensue. A children’s park train is involved. The story’s final image is grotesque, wistful, and wildly hilarious all at once.

Writer Richard Ford, in his introduction to The Granta Book of the American Long Story, tells us that novellas (typically running between sixty and a hundred and twenty pages in length) are “nicely suited to stories of character disintegration.” Frank deploys this trajectory with skill. As well as its opposite: characters circuitously winding their way toward wisdom and insight. In Frank’s novella “Biting the Moon,” the narrator shares memories of her romance years ago with a celebrity composer. The story grows increasingly fraught as she recalls drunken and abusive behavior from him. Her memories shift and mature as she confronts and interrogates them. Joan Frank’s novellas crystalize the passage of time in profound ways. The final two stories in Where You’re All Going, “Cavatina for Passenger X” and the title novella, channel Chekhov in their microcosmic portraits of community, friendship, marriage. (“Every marriage contained the seeds of its own end, happy and unhappy in almost equal measure until, by whim or accretion, the balance tipped.”)

Impersonal travel essays are nowhere to be found in Frank’s deeply personal collection of travel essays, Try to Get Lost. She is blessedly blunt about this turbulent era “of perhaps the most frightening protofascist ever to assume office in American history.” Her essay “Red State, Blue State” is a Baedeker for bad times. Survival strategies include everything from exercise to charity work to “you drink.” Pulling up stakes is an option, not a panacea. “Travel beats us up,” she admits in “Shake Me Up, Judy.” “Sleep’s elusive. Stress is amped.” Her sketches of European cities benefit enormously from shoe leather reporting (and the accompanying shin splints). The verisimilitude is breathtaking. Shop windows in Italy (“In Case of Firenze”) inspire a cinematic cascade of history and culture:

Itemize what you see: dusty, crumbling books, violins and mandolins, vases and dishes, forged bells, paintings from centuries-old flea markets, maps, inscrutable scientific instruments, decrepit birdcages, flags, buttons, globes, chess sets, rusting anchors, pulp paperbacks in multiple languages, bed-frames, empty bottles, belts, sconces, trays, mirrors, cracked pages from old botanical texts of hand-tinted prints torn out and framed. Etchings and woodcuts. Bad art. Bad furniture. Exquisite art. Exquisite furniture, draped with insanely expensive tapestries. Chandelier crystals. Kitchen appliances. Living room sets. Faience. Crates of tarnished, unmatched jewelry. Gilt sculpture. Murano glass. Religious icons. Life-sized statuary. Broken toys, cheesecake photos, unclassifiable objets from the 1950s. Wooden clocks painted in garish designs, pendulums ticking away.

“Place becomes, finally, the only subject,” she writes in “The Where of It.” “Place is identity, style, faith, cosmology.” Joan Frank’s own story is threaded throughout Try to Get Lost. “Cave of the Iron Door” is a searing essay about hard family memories evoked on returning after many years to her childhood home in Arizona. “Here was the original world,” she writes. “Your big bang.” Sadnesses endure. They travel with us. A lost museum ticket on a trip to Germany in “Little Traffic Light Men” triggers a welling up of grief for her recently deceased sister. (“Here’s a fact I can offer with authority: it is very hard to find places in a museum’s rooms where you can cry in privacy. Corners seem to work best, if you face into them.”) Try to Get Lost is superb travel literature. It might also be one of the best memoirs you’ll read this year.

-

In the Land of Men

In the Land of Men

Adrienne Miller

HarperCollins 2020Reviewed by Bob Wake

An instant classic. Adrienne Miller was the fiction editor at Esquire magazine in the late-90s when she was still in her twenties. Crossed paths with Mailer, Updike, Bret Easton Ellis, Dave Eggers, and, the real subject of her book, David Foster Wallace, whom she edited (some of his best short stories appeared in Esquire, including “Adult World (I),” “Adult World (II),” and “Incarnations of Burned Children”), and with whom she shared a romance, off and on, for several years. It’s something of a lurid tell-all (one review is titled “Infinite Jerk”), but offers lots more about the era, its literature, its sexism, and the rise and fall of glossy magazine publishing at a time when the Internet was just taking hold. Miller chose not to talk with D.T. Max for his biography of Wallace, so the material presented here is largely uncharted and eye-opening. Her respect for Wallace as a writer is worshipful. The mind games she endured during their wildly complicated relationship are jaw-dropping. The richest, fullest portrait of David Foster Wallace that has so far appeared in print. Highly recommended.

-

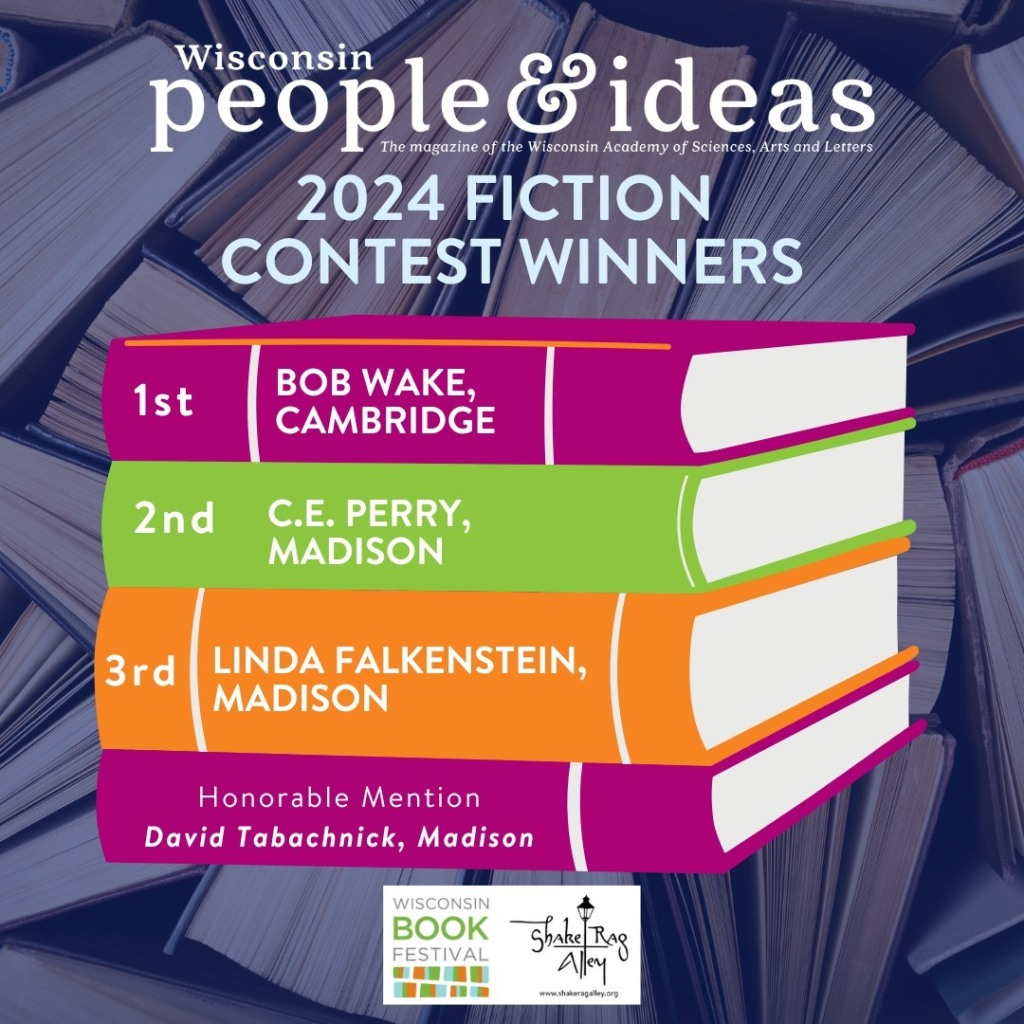

Mudstone

Thrilled and honored that my short story “Mudstone” won First Place in this year’s Wisconsin People & Ideas fiction contest. The story will appear online and in print next month in their summer issue. [Update 7/18/17: “Mudstone” can be read online here.]